Forestry and the use of wood are more controversial than ever. On the one hand, there is a conflation between shocking images of deforestation in tropical areas and the reality of the increase in the forest estate on the European continent. On the other hand, some members of the general public perceive wood companies and foresters as harmful to the environment and focused on profit. However, forestry and the use of wood play an essential role in meeting environmental commitments. While wood has always been a part of our lives, it is also our future.

WOOD IS DEFINITELY A MATERIAL OF THE PAST

While some claim that wood is a material of the past, it is unrealistic to argue otherwise.

From 58 to 50 BC, during the conquest of Gaul, Julius Caesar observed the vital importance of wood in the production of his armaments and the construction of his fortifications.

In 218 BC, when the Carthaginian general Hannibal aimed to conquer Rome, he quickly realised that to overcome the natural obstacles in his path, he needed wood, a lot of wood. Wood to warm his troops while crossing the Alps and more wood to build rafts and ships to cross the Rhône.

The oldest evidence of wooden furniture was found in the tomb of Queen Hetepheres I around 2550 BC and in that of Pharaoh Tutankhamun around 1330 BC. These pieces of furniture, including armchairs, beds, chests, screens, and sedan chairs, can be seen in major museums around the world.

In 1991, a mummy known as Ötzi, “the Ice Man,” was discovered in Italy in the Val Senales near the Austrian border. Ötzi dates back to the Neolithic period, about 5,000 years ago, and remarkably, he was found with his well-preserved equipment from that era. Wood is omnipresent in this equipment: a backpack and a quiver with hazelwood frames (Corylus avellana), arrows made of viburnum (Viburnum lantana) and cornelian cherry (Cornus mas), a dagger with an ash handle (Fraxinus spp.), a tool with a linden handle (Tilia spp.), a hatchet with a yew handle (Taxus baccata), and a bow also made of yew. Ötzi’s hatchet had a copper blade glued to the wood with birch pitch. Ötzi and his contemporaries had already understood and analysed the full range of properties offered by wood.

Given that wood is naturally biodegradable, traces of its use typically disappeared around 5000 BC. This was already a beautiful illustration of a material from the past. However, the explorations of Professor Larry Barham’s team from the University of Liverpool have changed this perspective. Their recent archaeological excavations were featured in an article published in November 2023 in the renowned scientific journal “Nature”. A wooden structure, assembled using a system of carved notches, was uncovered beneath a riverbed in Zambia. It was constructed 476,000 years ago!

This discovery raises the question of which human species was capable of creating such a structure. Homo sapiens have only been present on the African continent for about 300,000 years. It might have been Homo heidelbergensis, known to be in the region at that time. This Homo heidelbergensis possessed undeniable technical abilities, but their intellectual skills leave scientists puzzled.

What becomes entirely fascinating with wood is that it is deeply intertwined with human history and intelligence. No other material can claim the same. By tracing back half a million years, we can demonstrate how wood is a “companion material” that has always maintained a form of permanent modernity. What would we be without wood? It remains the cradle of our childhood and the coffin of our final journey. This companionship, which has spanned all eras of human history, is like old couples, so accustomed to each other that they no longer know how to appreciate one another.

But that is another story, the story of a material undeniably from the past, but also very much of the present and most certainly of the future. The material of all time, in short…

WOOD IS ABOVE ALL A MATERIAL OF THE FUTURE!

Wood has become so commonplace over millennia that we no longer question its timeless modernity. It’s about time we did…

If we recall Ötzi, “ the Ice Man,” our predecessor from 5,000 years ago, one piece of his equipment stands out: his yew bow. Why yew? It certainly wasn’t the most common wood in the forests of his time.

Although there was no such thing as wood science, observation, pragmatism and the diversity of species found in the forest more than made up for it. Ötzi’s bow reveals our ancient ancestors’ analytical capabilities. Today’s technology allows us to measure the angle of cellulose microfibrils (AMF) in the S2 layer of the cell wall, determining mechanical properties. The higher the AMF, the more flexible the wood. Yew wood has one of the highest AMFs, which Ötzi had already understood and utilised. He recognised that yew was also strong, stable, and rot-resistant.

In material sciences, we often seek a combination of properties to create future materials, such as rigidity, lightness, and low manufacturing costs. Ötzi’s story shows he was akin to today’s researchers. The hunter-gatherer was already in the modern era, and it was with wood.

Technological leaps, often synonymous with modernity, frequently occur in wartime periods. History is full of examples, and wood is no exception.

The first signs of a pronounced technological interest in wood can be found in the etymology of the term “engineer”. If we consider engineers as symbols of progress – which sometimes needs proving – the term “Angiguinors” appeared in 1248 during the Seventh Crusade led by Saint Louis. It evolved to “ingignours,” then to “ingénieur” in 1537, referring to specialists in designing and assembling wooden war machines. History likely forgot that the first engineers were wood specialists, making the engineers from ENSTIB the most etymologically accurate.

During World War I, wood research flourished, notably as the French Air Force in 1918 had over 7,000 aircraft, all built from wood. However, this intensive wood research declined gradually as societies embraced the notion that the newest materials were inherently superior.

During World War II, there was renewed interest in wood. The De Havilland Mosquito DH-98 fighter-bomber, used by the Royal Air Force and others, was primarily wooden, making it lightweight, fast, and with a low radar signature – earning it the reputation as the first stealth aircraft. And yet we still question wood’s modernity?

The role of wood in the development of both naval warfare and commercial shipping is well-documented. Without wood, it would have taken much longer for Christopher Columbus to discover the New World in 1492. Whether it was Amerigo Vespucci or even Viking expeditions in the 10th century, the fleets relied on wood’s rigidity and mass, or the Viking longships’ lightness and flexibility, placing wood at the forefront of modernity.

Beyond its ubiquitous daily use, wood is also an energy source.

Until the mid-19th century, wood was a key economic factor, mainly for its energy value, significantly aiding industrial development with charcoal consumption. This did not grant wood energy a modern image; charcoal burners were seen as poor, drunken poachers, far from modernity ambassadors. Yet, forges, lime kilns, glassworks, brickworks, and tile works were set up in the heart of the forest to obtain supplies of charcoal, often leading to local overexploitation – a practice to be avoided in today’s sensitive social context. Fossil fuels saved French forests from decline around 1800, with coal and oil replacing charcoal, leading to the remarkable forest area recovery in France, now covering 17 million hectares and still growing.

In the energy sector, renewable energies are an undeniable solution to the global warming that is disrupting our planet. In the collective unconscious, renewable energies are mainly associated with wind power, solar energy, geothermal energy and so on. All too often we forget what the real figures are. In France, wood energy dominates primary renewable energy production (36%, or 125 TWh), followed by hydro (17%), wind (11%), and solar (about 5%).

From humanity’s first encounter with fire, through the charcoal-based industrial revolution, to today’s energy crisis, wood energy has been a constant, unheralded presence. It remains modern and relevant.

The wood construction sector deserves extensive discussion, it being the economic engine of the entire industry. It epitomises wood’s modernity and relevance to contemporary global issues. Over a few decades, wood construction transitioned from traditional uses to high-rise buildings and urban projects, becoming a canvas for contemporary architecture.

Historically, urban buildings from the Middle Ages to the early modern era were mostly wooden. Over time, stone replaced wood in cities, relegating it to attics and roofs. During the 19th century, wood was gradually abandoned for load-bearing structures in favour of cast iron, reinforced concrete, and steel. However, in North America and Scandinavia, wood remained prevalent, unlike in France.

For a time, wood seemed forgotten by architects, nearly vanishing from French architecture schools’ curricula. The 21st century and new climate challenges changed this. Construction accounts for nearly a quarter of France’s CO2 emissions, with concrete as the main culprit. Among construction materials, only wood absorbs atmospheric CO2 through photosynthesis (sequestration). One cubic meter of wood stores about a ton of CO2 and replaces high-emission materials. Even legislators recognised this, with the RE2020 regulation aiming for carbon neutrality by 2050.

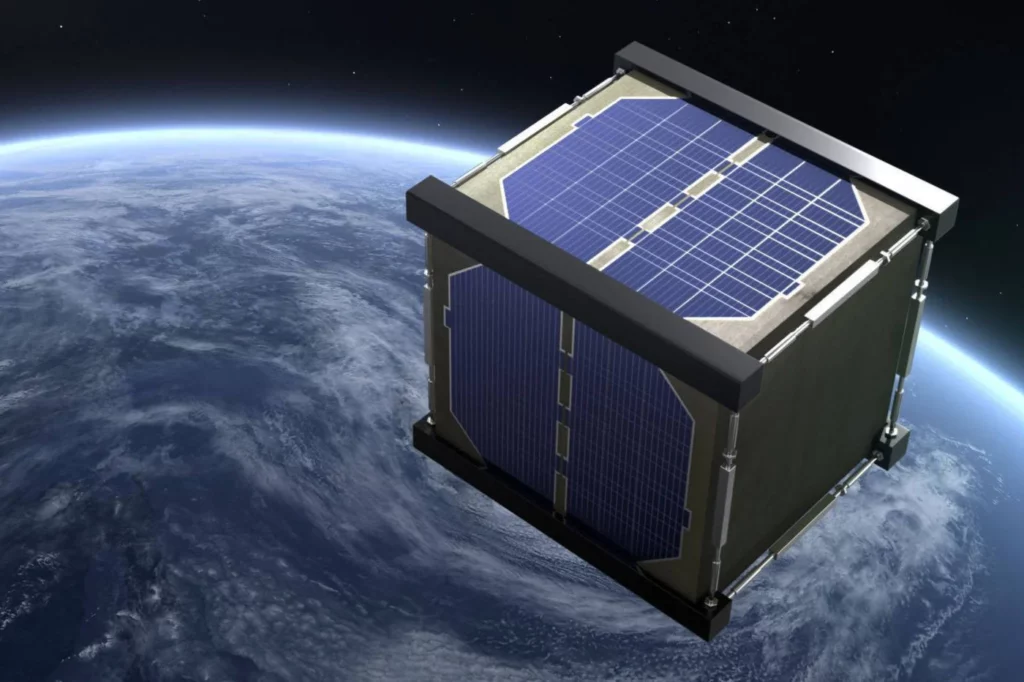

From Earth to space, a significant leap is underway. NASA and the Japanese Space Agency are developing a magnolia wood satellite, “LignoSat,” set to launch in 2024. Initial tests show no structural deformation in space, unchanged mass, and high mechanical resistance. The satellite withstands temperature changes and cosmic rays better than others. As space becomes cluttered, LignoSat’s almost complete combustion upon re-entry is a significant advantage, with potential future composting.

Wood’s modernity is ongoing, discreetly and silently, like the enchanting silence of growing trees.

In this regard, we can only draw inspiration from the reflections of Egon Glesinger, brought together in his book The Coming Age of Wood, published in 1943, partially based on his doctoral thesis defended in Geneva in 1931. His work was visionary. He already discussed the role of wood in the post-oil era and its essential place in construction. He mentioned the billions of destitute people in the post-war period, a parallel to the billions of climate refugees we face today. He addressed the industrial revolution within the wood sector, the necessary integration of the forestry and wood industries, the advent of wood chemistry, and the absolute necessity of planting more trees.

SO, IS WOOD: FROM YESTERDAY, TODAY, OR TOMORROW?

Historically, wood was one of the first materials used by humans, serving to build shelters, tools, furniture, and means of transportation. It played a crucial role in the development of civilisations.

Looking to the future, wood stands as a pillar of sustainable construction and design. Technological innovations have revolutionised its use, enabling the creation of larger and more resilient structures. These advancements pave the way for architecture that reduces the carbon footprint, addressing contemporary environmental concerns.

Moreover, as a renewable resource capable of storing carbon, wood fits into a sustainable resource management approach essential for combating climate change.

This duality of wood, rooted in the past while being future-focused, illustrates its capacity for constant reinvention. Therefore, wood is an essential material in the quest for a more sustainable and environmentally friendly future. Far from being a relic of the past, wood is a dynamic material that continues to evolve and adapt, meeting the challenges of our time.

ENSTIB (École Nationale Supérieure des Technologies et Industries du Bois) trains specialists in wood material. Their programmes include a Professional Bachelor’s degree in Wood Furniture or Wood Structures, a Master’s in Wood Construction Architecture, and Engineering degrees specialising in Wood.

Special thanks to Professors Pascal Triboulot and Marie-Christine Trouy for their contribution to the writing of this article.